There's this thing called UNESCO. It's a big acronym. What it stands sounds kind of pompus so you can have fun making up words that it stands for instead. United Nymphomaniacs Emasculating Sychophantic Christian Oppressors is a possibility to get you started.

HINT: Google it if you really want to know what it means.

Unflaggingly Naming Everthing So Cool Organization is another possibility. It is not as funny as the raunchier options, but not far off the mark of what UNESCO actually does. Everything UNESCO names as a World Heritage Site is always pretty damn cool. Three entire sections of Budapest are WHSs, Spisky Hrad (the big ass castle in Slovakia) is one, as are the painted monastaries in Romania. All were worth visiting.

There may be a bit of bias in what's picked, though: if you look at a map of World Heritage Sites, they are mostly concentrated in Europe. Also, in a possible cultural middle finger to the USA, most of America's World Heritage Sites are national parks: the Grand Canyon, the Everglades, etc. In fact, the only USA WHS (more acronyms) actually produced by America society is Monticello. Hint: Monticello was Thomas Jefferson's home (don't feel bad if you didn't know that; I had to google it to make sure). But basically UNESCO seems to be saying that while Europe has made many things of cultural import, the only things worth preserving in America are those things that were there before we arrived.

In any case, bias aside, I have come to respect UNESCO's choices and try to check out World Heritage Sites whenever possible. So when I learned that one of UNESCO twelve most priceless treasures was in Poland, I decided that I had to see it.

It was a salt mine.

Yes, a salt mine. We'll get to it in a second.

I met up with two of my good friends in Peace Corps, Sean and Seth, in Krakow, Poland. They were heading west, coming from Lviv and going to Budapest. I was going in the exact opposite direction.

Let me say that Krakow is absolutely beautiful.

Never heard of Krakow? You will one day. More than once I've heard that Krakow is the next Prague and that Lviv is the next Krakow. That sounds really In-The-Know, but it just sums up the travelers philosophy: "if I didn't have to go through hell to get there, it wasn't worth going."

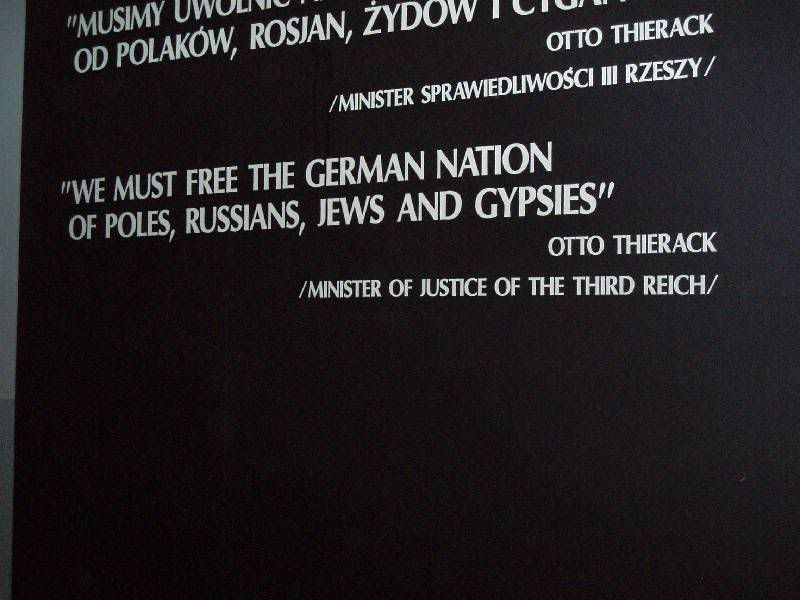

Prague, Krakow and Lviv are all amazing cities, but to a traveler they rank thusly: Prague was once the darling of the backpacker circuit but is now full of tourists and therefore must be disdained. Krakow is not as touristy but easy to get to due to EU subsidies, letting visiting backpackers feel special but not having suffered overmuch to do so (other than, *ahem*, getting chloroformed on a train). Lviv--plagued by visa, language, lodging, transportation and service problems--is only visited by the most hardy travellers, i.e. Australians and Peace Corps Volunteers. Actually, when I was in Lviv in Feburary, I didn't see a single non-Ukranian there. In fact, the last time a large group of tourists actually visited Lviv, they killed all the Jews and shipped back thousands of tons of topsoil to Germany. This probably explains the lack of hostels.

Yes, to a rough and rugged Ukrainian Peace Corps Volunteer, Krakow is not off the beaten path, but is instead a substitute for heaven, ripe with soft toilet paper, West Slavic language and cute Polish girls.

But I digress.

Where was I? Oh yes, salt mines. We're getting to that.

So I met Seth and Sean in Krakow. This is me with Sean and Seth:

I'm wearing the Prague tee-shirt that Anna bought me to make up for loosing my other one. And Carrie has already pointed out that I look scrawny compared to Seth and Sean, so you don't have to comment on it. Sigh. I hate having my self delusions shattered the harsh facts of reality.

That's part of the Krakow castle in the background (we're inside the walls). Krakow castle was listed as THE thing to see in Poland by the Let's Go travel guide, which either doesn't speak well of the rest of Poland, or speaks a lot about Let's Go's leanings towards hyperbole--and its inability to correctly report which of Budapest's baths are the gay ones.

But again I digress.

What a fun phrase. Who, I wonder, came up with this magic set of words that lets you ramble on unchecked and yet still be forgiven by a reader for your self-indulgent meanding simply by stating three little...

But I digress.

All this should be giving you the clue that there wasn't a lot to the salt mines.

Also, Let's Go was the one that said the salt mines were one of UNESCO's 12 most priceless treasures. The problem is, while the salt mines are on the world heritage list with several hundred other places, I have found no mention to a priceless treasures list outside of Let's Go. I'd like to know what the other 11 are, but I don't think I'll ever find out because I suspect that such a list doesn't really exist and am starting to really suspect that Let's Go is full of [expletive deleted].

Anyway, the castle was fun, it simply wasn't as remarkable or photogenic (the really important quality in a castle, defensibility be damned) as other castles I've been to. After seeing the castle, we hopped on a marshrutka (or, as the Polish call it, a "marshrutka") to the town of Wieliczka.

We were left at a grassy patch by the road and, after walking past some abandoned factories, found three boys in a cement culvert who managed to point us in the direction of the mines.

There, we found many brand new tour buses, forcing us to wonder just how Off-The-Beaten-Path this was. Answer: not very. I paid for our tickets with my Visa check card and then we were led by our English speaking guide down a set of 850 stairs (I kid you not) into the 350 km worth of tunnels that make up the salt mines. Also down there were a couple of underground lakes, so saturated that they simply could not absorb any more salt and are now impossible to drown in (well, almost; several Soviet soldiers were on one of the lakes in a rowboat. It overturned, trapping them underneath and pushing them under the water, where they then drowned. This is why communism failed).

These salt mines were once the source of great Polish wealth, back when you could receive your salary in salt because rotten food just didn't taste the same without it. Yes, yes, I know that's wrong. I know that salt was important because it was used for preserving meat, but I once had a seventh grade Language Arts teacher tell me the former answer when I asked her why salt used to be so valuable the Roman army was paid in it. It was only many years later that I realized she was as full of [explitive deleted] as the Let's Go guide.

Okay, now to the real reason these particular salt mines warranted UNESCO's attention: miners got bored and miners were religious. This led them to carve salt. Lots of salt. Into--mostly--religious statues. Down in these mines are dozens and dozens of statues carved out of salt, as well as several chapels, also carved out of salt.

I will have to admit the salt carvings were pretty cool. Ditto the chapels, which had chandeliers not made out of glass, but pure salt crystals. The coolest part, though,--the hippest, the most heater, the most sick, the most gnar--was the fact that you could lick the walls. They tasted salty.

Also, for a scare: the timbers supporting the roof of the tunnels (which was also salt) were 400 years old. Most people replace wood by then, but because the salt had petrified the wood, it was deemed safe to let the really, really, really old wood be the only thing that kept tons of salt from collapsing onto the heads of hundreds of tourists. Who's with me in trusting the assesment of mine saftey by a newly emerging, formerly-Soviet country? Anyone? Anyone?

And one last thing before we just get to the pictures, which you've no doubt skipped over all these words to see anyway. Some of the oldest sculptures (at 600 years old) had weathered away to almost featureless. This was in sharp contrast to other, newer, very beautiful sculptures had been intricately detailed in this very impermanent substance. I asked our guide what measures they were taking to preserve the newer (and by newer, I mean 150 years old) sculptures. "Nothing," she said. In other words, in 50 years, when Krakow is the new Prague and Lviv is the new Krakow, all those tourists won't get to see the same level of amazing details as I did. Which is why one tries to get a little off the beaten path.

But hopefully by then, they will have replaced the one four-person elevator that was the only route back to the surface. The tour was two hours. Wait time for the elevator? An hour and a half. So sometimes it's not bad when, like a red-headed stepchild complaining ther her food tastes bland and could really use some, um, pepper, the path is beaten.

Sean, holding his hands under water pumped out of the mines. It looks like (insert Dr. Evil voice) liquid hot MAG-ma.

Sean, holding his hands under water pumped out of the mines. It looks like (insert Dr. Evil voice) liquid hot MAG-ma.

Oh, yeah, the legend of the salt mines: a Polish princess was allowed to throw a ring and whatever the ring touched, that would be for her people. It landed in a field and when the peasants dug down, they found the salt that would bring so much wealth to Poland. This is the ring being returned to the princess. Actually, modern archeology shows that tribes had been mining the salt for thousands of years, but who needs scientific fact when you have a cool salt sculpture?

One of the chapels, carved entirely out of salt.

One of the chapels, carved entirely out of salt.

A crucifix carved out of salt.

The Last Supper carved out of salt. When Jesus said "take this bread and eat it", do you think any of the disciples added a certain condiment?

Lastly, yours truly licking the salt

One of the chapels, carved entirely out of salt.

One of the chapels, carved entirely out of salt.