|

| Waiting for the race to start. |

Okay. Mission Accomplished. I am impressed.

It was 9:00 AM, and I was waiting, along with 19 other people, to compete in Zhytomyr’s Extreme Marathon, a multi-sport adventure race. This was actually only a mini-Extreme Marathon. The real one, in which I had competed the year before, was a 24 hour endurance race of running, swimming, climbing, ropes course challenges, orienteering, biking and rafting. Another volunteer named Carrie had been my partner, and we had lasted about 12 hours before Carrie's hurt knee caused us to drop out. Still, of the 32 teams from 6 countries in the race, four others dropped out before us, which meant we weren’t complete losers.

Although Extreme Marathon was born in Zhytomyr, its increasing popularity and the addition of corporate sponsorship (from Marmot, among others), meant that a much larger Extreme Marathon had taken place over the summer in the Chernitskava Oblast. Jon and I had briefly considered entering, took one look at the gear list and the hassle of getting it all to another oblast and, with Run Across Ukraine taking up most of our energy, decided it wasn’t worth it.

So I was excited when I heard there would be a smaller version in Zhytomyr. Unfortunately, Jon couldn’t leave his town because it was his last weekend in Ukraine, so I asked my neighbor and 15 year-old climbing protégé, Igor, to be my partner.

Right after he eagerly accepted the offer, he said with great earnestness: "I have only ridden a bike once, so we will probably loose."

“I’m not doing it to win,” I said to him. “I just want to finish.” I considered that for a moment, and then said: “And not come in last place."

Not only would we not fully complete the race, but we would, in fact, coming in absolutely, dead-last place.

Here is a record of how I screwed it all up.

***

Igor has an enviably sincere, can-do attitude, which is what makes him such a great student in class and one the cliffs. Right after accepting my invitation, he asked to borrow a bike so he could learn how to ride it. After I gave him one, he went off and practiced for the next four hours. When he returned it that evening, he asked to borrow it at 7:00 AM the next morning to practice some more. I woke up just long enough to give it to him before going back to sleep, trying to get in another hour in before having to leave for the race. Unlike his lazy American partner, Igor was up with the sun, teaching himself to ride.

|

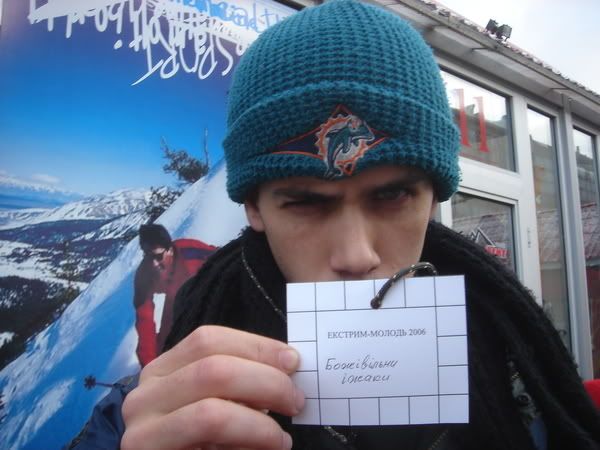

| The registration car hood, er, table. |

In the parking lot, ten teams were registering at the organizer’s table, which was actually the hood of a car. Once we signed in and paid 10 hrivna ($2) per team, we were given cards to go around our necks. These cards would be hole-punched and scrawled on at 18 checkpoints in and around Zhytomyr during the race in order to prove that we'd completed all of the race's challenges. When they asked for our team name, I gave them the one that Carrie and I had chosen the previous year: Bolshevilne Yeedjike, or “Crazy Hedgehogs”.

|

| Don't mess with the Crazy Hedghogs |

|

| Igor and I before the race. |

It didn’t really occur to me how spectacularly I was going to get my ass kicked.

All the teams lined up

We were handed a typed set of clues in Russian (“the hole puncher is inside an old well”, for example) and a map, which had the 18 checkpoints marked on them and the order they were to be done in.

On your mark, get set …

And we were off.

***

As a mob of 20 bikers, we made our way to the first checkpoint, which, once off Zhytomyr’s streets, meant navigating down a steep, hill-hugging, winding, muddy path. In the spirit of racing, I did not walk my bike down (two teams choose to do so), but blithely followed the psychopathic people ahead of me, waiting to fly off the path and die at any moment.

After braking to a dirt-spewing halt, we hopped off our bikes to gather around an old stone well, reaching down to punch our cards with a hole puncher tied to the inside. A code (B7) was spray painted on the side of the well, and this was then written by us on our cards next to the punched holes (each puncher left a different configuration).

And then it was off to the next checkpoint.

Except Igor’s bike chain had come off. And not just come off, but had inexplicably come over the gear wheel and was now around the pedal, jammed in against the gear shift. I hurriedly worked it back into place as seven teams disappeared off into the woods.

The chain now on, Igor and I crossed a wooden footbridge and furiously biked off after the other teams. On top of a hill, we couldn’t see them, so I reached for the map.

My hand felt cloth.

There was no map.

After the first checkpoint, I had shoved it in my left jacket pocket.

It was not there.

My pumping legs must have knocked it out.

Fuck.

Leaving Igor at the top of the hill, I went back the way we came, looking for the map. The other two teams, the ones that had walked their bikes down the hill, passed me. I went twice along the distance between the hill and the first checkpoint and could not find the map. Possibly someone had picked it up; there were Ukrainians walking along the paths we were riding on. Possibly one of the two trailing teams had grabbed it, but that was unlikely. Ukrainians are remarkably sportsmanly. It had occurred to me to stop one of the trailing teams and ask them to share one of their maps, but I knew that they would say yes and that it would be unfair to impose ourselves on someone for the entire race.

In the end, Igor and I went back to the starting point and got another map.

That was Daniel mistake #1.

***

New map in hand (firmly clutched in hand), it occurred to me to skip the next checkpoint and catch up with everyone (there’s a 30 minute penalty for each missed point), but I wanted to do the whole race. If I was going to loose, I was going to at least complete it.

Half an hour later we were lost in the woods. There was a circle on the map on a green bit and there was a clue for a “half ruined tree”, but after a lot of circling, we couldn’t find that tree. Found a lot of live ones and a few dead ones, but no “half-ruined" ones that would have a hole puncher and a code. The forest was a maze of crisscrossing paths and while I could always get us back to civilization, I didn’t always know where we were in relation to that circle.

My mobile rang.

“How’s the race?” asked Jon.

“Igor’s bike chain came off, I couldn’t find our map and now we’re lost in the woods.”

“Huh,” said Jon, helpfully.

“And we haven’t even reached the second checkpoint.”

“Yeah, sounds like you’re doing well,” said Jon. “Good luck, then.”

After more of not finding that tree, I decided that we’d have more fun doing the climbing challenges that would come later, and didn’t feel like spending any more time wandering around frozen in the woods. We were going to loose anyway, why worry about a tree?

“Let’s go, Igor,” I said.

***

At the next checkpoint, we found lots of bikes leaning against trees. It was the orienteering section, which was meant to be done on foot.

The check-in for the orienteering section

Two race volunteers were checking teams in and out, writing their times on a clipboard. I looked at it. A team was actually still behind us. Apparently they’d had a bike problem. Five other teams were out in the woods. I looked at the three teams that had finished this section. They’d all taken around 45 minutes to find four points which were out in the woods, and they’d been the fastest. According to the times, some teams had been out there for more than an hour. It had been snowing for a week in Zhytomyr, and had all that snow had melted in two days of above-freezing temperatures. Although it had been below-zero in the morning, it was back up now and the whole forest was mud. Still, I’d been sweating under my sweaters (they finally lived up to their names) and now felt like I was freezing with their wetness against me.

“Want to do this?” I asked Igor.

He shrugged. “Whatever you want to do,” he said.

Walking around cold in the mud for an hour?

“Yeah, we’re not going to do this part,” I said, handing the map back.

The race volunteers balked.

“We know we’re going to loose, so we’re going to keep it fun,” I said.

They laughed and waved us good luck.

Igor and I went to the next point.

***

The next checkpoint actually was fun: we found ourselves under a large bridge over a small river. Two more race volunteers were there and the challenge, as they pointed out, was to climb up the inside of the bridge, walk across the scaffolding under the bridge (clipped into a rope they’d strung the length of it), hole punch your card with the puncher dangling from underneath the bridge and then rappel down.

Finally, something worth doing! I strapped on my harness and began climbing, got to the scaffolding, clipped in and began dodging around steel beams, pulling myself through holes made by their “X”s, clipping in on one side of the hole and unclipping from the other. As I navigated under the bridge (the Red Hot Chili Peppers song starting in my head and not leaving for a long time), Igor snapped pictures of me.

Climbing under the bridge

In the pics above and below I am rapelling down

Rappelling down, I was now halfway down a steep, concrete embankment leading to the river. Rather than go up the embankment and bike across the bridge, though, the volunteers were telling us we had to cross the river.

Looking down, I saw one of the teams ahead of us doing so. Looking back up, I saw Igor lifting a bike over the barricade.

“Wait!” I yelled, but he had already let go, the bike sliding on its side and smacking into my outstretched hands a few seconds later, but not before the front reflector had broken off.

“Was the bike injured?” Igor asked me in his not-always-perfect English.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, the bike was injured.”

“Oh no!” he said earnestly (if there was a Ukrainian version of “Leave it to Beaver”, Igor would be its star).

I climbed up the embankment, shouldered the other bike and began carrying it down, which really meant I was sliding on my ass, trying to keep my hands away from the broken glass, the remains of decades of idiots tossing beer bottles from above.

Carrying the bike down the glass strewn embankment

This wasn’t just extreme, this was Ukraine extreme. If my feet slipped, I’d go tumbling down to the river, tangled up in ten pounds of bike. This is always what scares and excites me about Extreme Marathons: real danger. In America we have a lot of fake danger: jumping out of a plane with a parachute is scary, but you’re only going to get killed if two sets of equipment fail, which part of you realizes isn’t likely. It’s adrenaline without real fear. Real fear was last year, where getting to one hole puncher meant climbing down a well, feet braced on one side and back on the other, a rushing underground river at the bottom, no protection if I fell. There is no culture of litigation in Ukraine. If you get hurt from doing something stupid of your own free will, a Ukrainian judge will laugh if you tried to sue. So dangerous challenges that would give an American organizer pause are nothing to Ukrainians; in fact the participants seem to have a certain relish for them(we are talking about a country that birthed Leopold Von Masoch, whose writings gave us the word Masochism). And even though I’m an American, even though there’s no way in hell I’d, say, climb down that well for the fun of it, in the middle of a race and hopped up on competition, I hadn’t thought twice about going down it. And now, part of me was wondering why I was sliding a bike down this embankment, but it was only a small part, one quickly shoved away by the concentration of survival.

Igor getting his bike down to the river

We got the bikes down, adrenaline making my muscles vibrate, and began carrying them across the rocks poking out of the river. I had thought to wear my waterproof boots for the race, but they’re heavy and thought my cheap-but-light sneakers would fare better on a race that was mostly biking. This is what I get for thinking.

Bam, my foot slips and is plunged into the freezing water. Igor fared worse, getting both feet wet. On the other side, frost formed on our shoes. I wrung out my wet shoe (the pair was $10 at the bazaar; the soles are so thin that I can literally wring them out) and my sock before Igor and I manhandled our bikes up the grass on the other side.

Some of the teams behind us, bringing their bikes down the embankment and beginning to cross the river

I was slightly frustrated at the experience. We could have gone across the bridge, but it seemed like the race was being extreme for the sake of being extreme, making us go down the embankment, across the river and up the other side. Later, I realized why that was.

At the top, we began biking some more. According to the map, the next street would take us directly to the next checkpoint: a graveyard. But there were no side streets for quite a while. According to the scale of the map, we should have hit it already, but we hadn’t seen one. Looking behind us, I saw another team of bikers, so we must be going the right way.

Turned out, they were following us.

The street, I realized, was the dirt road that was on the other side of the river. I thought the street we were supposed to get on was paved: we had biked on it earlier in the day and that section had been blacktop. On the map there was nothing to indicate that it turned from paved into dirt, but it did. That was why they sent us across the river: the road was right there.

By the time I realized the mistake, it was better just to cut south and try to reconnect to the road later, the other team following us the whole way. Despite skipping two checkpoints and getting back in the pack of teams (and being spatially, if not technically, ahead of six other teams), the roundabout way of getting to the graveyard meant that we and the other team were now in last place. Except the other team had done all the checkpoints, and Igor and I were about as far behind as we could possibly be.

That was Daniel mistake #2.

***

We stuck with this other team, more or less, for the remainder of the race. Its members were Dima and Irka, a boyfriend/girlfriend team that Carrie and I had spent most of the last Extreme Marathon trading places with. It seemed fitting.

In the cemetery, our next checkpoint was to write down the day that Karol Something-Or-Other died. If “Karol” doesn’t sound very Ukrainian, it’s because he and most of the other occupants of the cemetery were Polish, having been buried at a time when Poland controlled Ukraine. We found his grave, a huge one, behind the cemetery’s tiny church.

Igor, biking ahead of me in the graveyard

We wound our way out of the city and back into the country, crossing another footbridge and temporarily interrupting the four adolescents that had been smoking cigarettes and fishing there (even after two years of living in Ukraine, it still surprises me to see a 12 year-old puffing). We found our next checkpoint code spray painted on a pipe dumping strange contents into the river, found the next one spray painted on some small cliffs a half-mile past it.

Above, Irka crossing the footbridge with the smoking/fishing kids. Below, two more of the kids, one still holding his cigarette

We possibly found some criminals as well. Two guys were using a cross-cut saw to cut firewood, watched by two other men (there’s a Ukrainian proverb that goes: there are three things a man can always watch: fire burning, water flowing and other people working). One of the guys cutting had lost an eye and had a slash across it that looked like it came from a knife. The whole tableau looked interesting and I asked to photograph them. I’ve never had a Ukrainian refuse to have their photograph taken, but they did and began looking around, slightly worried that I had asked. I decided it was best to keep moving.

Irka biking past hills covered in frost

Dima, Irka and Igor carrying their bikes over some rocks

I did like that about the race: it put us into contact with a lot of people going about their daily lives on a Saturday, showed me a lot of areas of Zhytomyr I had never seen before. I probably saw more new things in Zhytomyr in the six hours of the race than I’d seen in the past six months.

In the pics above and below, some of the scenery around Zhytomyr

***

Despite the newness, I was extremely familiar with the next checkpoint: it was the cliffs I had been climbing on for over a year. Getting there meant lugging the bikes up to an overpass, crossing to the other side of the river and then lugging them back down.

Carrying the bikes up to yet another overpass

At the cliffs, we were required to climb a route to get our cards signed by one of the volunteers there. The route I had to climb was one I’ve climbed at least 50 times before: a sweet, easy little crack that shoots up for 70 feet. Except I had never climbed it in wet, muddy, $10 tennis shoes after spending four hours biking. My feet kept slipping and I ended up climbing the thing hand over hand, absolutely exhausted when I got to the top. Igor, who had been belaying me, gently lowered me down.

“Good work!” he said, trying to encourage me.

I nodded, too out of breath to speak.

Irka was climbing the route beside mine, with Dima belaying her. She was only halfway up and, not wanting to get any farther behind, Igor and I set off.

Igor goofing off

Our next point was down a well again, me holding Igor’s legs so he could lean in and punch the card. Igor had begged off the climbing challenges because he was tired from the biking. I honestly thought Igor wouldn’t have much of a problem during the race, because he has a lot of endurance. He often goes jogging with Jon (who regularly runs marathons) and, unlike me, is always able to keep up with him. Still, even though he didn’t seem to be uncomfortable on the bike, he was constantly trailing behind me. So, because he seemed more tired than I was, we had reached an unspoken agreement: I climbed things, he crawled into things, which is how he ended up half inside a well.

Igor in the well

Irka and Dima biked past us a little later, while I was Daniel mistake #3, which was to ask an old woman how to get to another street. Ukraine doesn’t have street signs. The street names are stenciled onto buildings when someone decides to mark them, which isn’t often.

I was asking her how to get to a lake that was on the map, which was the next checkpoint. She kept trying to get me to go to the river. "The river is a much nicer place to go," she said. She didn’t really get that this was a race and I needed to get to the lake. “Go straight and then take a left”, she said. I knew a left would get me to the river. Irka and Dima took a way I had suspected would get there, but also suspected would leave us lost in a bunch of unmarked cross-streets. The problem with not growing up in Zhytomyr is that I don’t really know the place. I wanted to get out to a main road and take it up towards the lake.

Of course, I was now trying to get away from the old woman, who didn’t want to let go of my map and didn’t want to stop telling me how to get to the river. Two other old women came up and they all began arguing over which way I should go.

I gave up on directions to the lake. “See this road?” I asked pointing to a main one. “How do I get there?”

One of the old ladies pointed at a building. The main road was on the other side, she said.

“Thanks.”

Igor and I biked past some old playground equipment, crossed in front of the building and headed up the main road.

***

We found Dima and Irka at the lake. The clue said the hole puncher was attached to the small dock there, but they hadn’t found it yet. Igor did his job and, legs on the dock and torso wrapped under it, managed to see where the puncher was hanging. We passed him our cards to punch, and then moved onto the next challenge, in a wooded area of Zhytomyr.

Dima, Irka and Igor at the dock

Dima and Irka were leading the way, so they got to do the challenge first: paintball.

I had been excited about this bit, and it was partly why I had skipped out on the orienteering. I thought paintball would have all the teams pitted against one another, and I thought that if Igor and I got too far behind, we’d miss out.

Actually, each team of two was pitted against snipers. This was the way it worked: five wooden targets had been nailed to trees. You and your partner shot the first two targets to learn how to use the guns, then lit and threw a smoke grenade into the woods. You were then supposed to use the smoke as cover as you went deeper into the woods to shoot the other three targets. The snipers (two of the guys working for the paintball company) tried to kill you and you tried to kill them, or at least survive long enough to shoot the targets. You got your card punched whether you won or not.

Dima and Irka playing paintball

Dima and Irka were soon killed and Igor and I began pulling on the gear: pullover plastic camo pants and a jacket, kneepads, a bandanna, and a vest that held the CO2 canister for the paintball gun, which looked like an M-16.

In the pics above and below, Igor and I getting suited up. I'm on the left.

I was handed a smoke grenade and one of the snipers explained how to use it. There’s still a lot of words I don’t know in Russian and to me it sounded like this: “You see this hurgle? You pull it to pull the cap off one end and then you pull this hurgle on the other. Inside is a blibity and you light that with this lighter and then you throw it. Understand?”

And I said yes because the hurgles were obviously the cloth strips on both ends and a blibity had to be a fuse.

The snipers disappeared into the woods and, shortly thereafter, Igor and I ran in after them. We shot the first two targets, then hid behind a tree while paint balls exploded around us. I pulled one end off the smoke grenade, then the other. Inside one end there was nothing and in the other there was a metal ball. Now, I don’t know about you, but I’ve never lit a Russian-made smoke grenade before and was a little stumped. I’ve never so much as lit a firework while in Ukraine and so didn’t realize that there was a different way to do it. I held the lighter to the metal ball for a few seconds and then stopped, deciding I didn’t want to blow my hand off.

“Just go!” I said to Igor, dropping the grenade and shooting at the snipers, making them get their heads down. They ducked behind trees, and Igor ran out and shot one target, then the next. He started shooting at the third, then realized he had no bullets. I found that I was out of bullets, too. They’d only given us ten or so each and we’d used them all.

Igor dropped to the ground, lying on his belly in the leaves.

“Go on!” yelled one of the snipers.

“I’m out of bullets!” yelled Igor.

“Me too!” I yelled. I thought this mean we were finished, done, game over. But apparently the snipers didn’t think so.

“Then get back to the start!”

“But we don’t have bullets!” I yelled.

“Go back!” they yelled again.

They wanted us to run with them shooting at us?

Igor started to get up.

“Go! Go!” I yelled, shooting my gun. Yeah, there were no bullets, but it still made a popping sound when I squeezed the trigger and that made the snipers get behind the trees, thinking that I had lied to them. Igor ran past me and I began to run as well, zigzagging as a small firestorm of paint balls hit the trees around us.

We finally got back alive, and, soon thereafter, the snipers came out of the woods, asking what had happened with the smoke grenade. I told them it didn’t work. We went back to where I had left it by the tree.

“Hold the lighter to it,” one of the guys said.

I did, and after a few seconds nothing happened.

“Keep holding it,” he said.

Finally, the metal ball must have heated up enough to ignite an internal fuse because sparks began to come out.

“Throw!” the guy ordered.

I did, and out came the smoke, quite uselessly at this point.

Still, it was pretty cool.

Me, coming back from having lit the smoke grenade, which is going off in the background

Stripping off the gear, I had wondered how paintball could possibly be included in a $1 per person entrance fee for the race, but as the owners were asking us if we liked it, told us about prices and handed us business cards, I realized how smart the organizers were: each team gets a little ten minute experience with just couple dozen paint balls and a smoke grenade and no doubt wants, like I did, to do it again and this time with a full magazine of bullets. Paintball hadn’t been part of the entrance fee; the paintball guys had donated it to generate business. Pretty smart.

***

We caught up with Dima and Irka at the next checkpoint. Although they had left fifteen minutes before us, they must have gotten lost. Igor and I had almost gotten lost as well, our dirt path through the woods disappearing and us breaking trail on our bikes, mowing down grass and brush as we raced past abandoned houses in the woods. The reason we didn’t try to relocate the path was that wild dogs were chasing us.

We’d been chased by dogs all day. It’s part of what makes an extreme Ukrainian race so extreme. But in the city, the dogs, which generally make up the totality of any given Ukrainian home security system, never chase you past the territory of the house they guard. But these dogs didn’t seem to have a territory and chased us all the way down to the river. For the tenth time that day, as they were nipping at our pedaling heels I thought: “We are going to die.”

As is, the river was our goal and we followed it to the next check point: an abandoned house that stood on a bluff overlooking the water (the property alone would be worth tens of thousands in America). Dima was climbing the tree in front of it, trying to reach hole puncher at the top. He wasn’t tied into anything; that wouldn’t be extreme. Rather than risk death yet again, I handed Dima our card and he punched both while I watched the sun start to set.

Dima up in the tree

As we got back on our bikes, it became obvious that we wouldn’t finish the race. No matter how many checkpoints you finished, all teams had to be at the finish line at 4:10 PM, six hours after the race started. We’d be lucky to get two more checkpoints in.

We biked, pushed said bikes and carried said bikes along the river, crossing intersecting streams and moving over and under fallen trees and along the edges of cliffs.

At one point, I was charged by a goat. A woman was sitting in a wooden rowboat beached beside the river, watching her three gazing goats. I stopped and took a picture of her and one of her goats must have thought this was threatening because it began running at me, head lowered. I was quickly starting to pedal when she yelled at it and it stopped mid-charge. I didn’t even know you could train a goat like that.

The lady and her goats. The one in front is the one that charged me

Charging goats? They forgot to put that in the race description.

Two checkpoints later we were at another favorite Zhytomyr point of mine: the riverside cliffs that Marina and I had climbed on all summer.

The challenge there, the last for us, was to rappel down to some rocks sticking out of the river, punch the card and then jumar up the rappel rope to the top. If you don’t know what a jumar is, imagine a metal handle with a wheel on it that only spins in one direction. If you clamp it on a rope, it slides up, but not back down. Jumaring up a rope uses two of these: one with webbing attached to your harness, one with a piece of webbing you put your foot in. You stand up on the webbing, lifting your body up, then slide up the jumar attached to your harness. This lets you sit into the harness to take weight off our foot and slide that jumar up in order to stand up on it again. This is done on straight ropes where there’s no way to climb up the rock, as was the case now because they’d hung the rope off an overhang, which meant it went 70 feet straight down to the river and those rocks.

Rappelling down over the river, the sun setting and turning it red and orange, was amazing. Jumaring back up after all the other exertions of the day? Stand up, slide up one jumar, sit down, breathe. Breathe. Breathe. Slide up other jumar, stand up, slide up first jumar, sit down, breathe. Breathe. Breathe.

Breathe.

Breathe.

Breathe.

One of the race volunteers

When I got to the overhang, I didn’t so much pull myself over the top as crawl and then roll and then lie there. Dima took the jumars and rappelled down.

Dima jumaring back up

Here you can see the mechanics of jummaring: the top jumar goes the the harness, your foot is in webbing attached to the bottom one

I wasn’t in a hurry to get up because we didn’t have enough time to do the last three checkpoints. I was happy about that, though. The next checkpoint required finding another tree. I don’t like finding trees because if there’s a problem with forests, it’s that it’s full of them.

I photographed Dima coming over the edge, felt a bit of satisfaction that he, taller and more muscular than I, a veteran of a number of adventure races, was just as exhausted as I was when he got to the top.

The four of us biked to the final stop, on the other side of Zhytomyr. Perhaps knowing it was the end, Igor, who had been trailing all day, was now right behind Dima and both of them sped ahead of me. Irka ended up falling way behind. Igor and Dima didn’t seem like they wanted to slow down, though, nor were they looking back, so I was in a strange tug of war trying to keep up with them ahead and trying keep Irka in sight behind. Finally I got stopped at a traffic light and Dima and Igor disappeared completely.

I pulled out a map and Irka caught up, saying she knew the way: it was to a factory that made climbing harnesses and sleeping bags. I had no idea that Ukraine had a company that made climbing harnesses, let alone one with a factory in Zhytomyr.

I let Irka lead, which is how I was the absolutely last person to reach the finish line.

***

Inside was a thing of beauty: a table laden with food. Igor, who hadn’t brought any food for the race, had eaten most of mine, and we had run out hours ago. Since Dima and Irka kept us racing hard, we never gave ourselves time to so much as stop to grab a candy bar. I had also been freezing all day, and the wisps of steam from the hot tea on the table called to me.

The most beautiful sight in the world after a race

Our card, after all the codes and hole punches

After everyone was inside the factory and they’d collected our cards to determine placement in the race, we were invited to eat. And as soon as we got up to move, though, the race coordinator asked us to go outside. Apparently the others were as hungry as I was and there were a number of protests. Still, we shuffled back out into the cold to line up in the dark for the awards ceremony, the food untouched.

Above and below are pics of the awards ceremony

Igor and I, as we suspected, placed tenth out of ten, but we got the prize everyone else did: free tee-shirts (again why I love Ukraine: I paid $1 for an adventure race and along with everything else, it included food and a tee-shirt). Third and second place got lanterns and I’m not sure what first place got because by then it was too dark to see.

The tee-shirt I got

We shuffled back in and pigged out.

***

“Seriously, let’s take a bus,” I said to Igor after about an hour of eating, talking and watching the video from last year’s Extreme Marathon.

Outside, it was back to below-zero and all my clothes were still soaked with sweat. My legs ached, and I was very, very tired.

The factory was located on a main road that ran straight (but for several miles) back to our apartment building. Any bus running along it would take us and our bikes home for the bargain price of 12 cents each.

“We should bike home!” said Igor. “We should finish on our bikes!” Despite his being tired all day, he must have processed that food pretty fast. Kids.

“Igor, it’s dark and we’re likely to get hit by a car,” I said. It wasn’t just an excuse: Ukraine is lacking in the street-light department, as well as in the sane-drivers department.

“So you’ll take a bus home and I’ll bike, okay?” he said.

He was determined to ride home, and I wasn’t going to let him go alone.

Fine. I got on my bike and listened to my legs cry.

And then another thing happened. During the day, Igor (when he wasn’t way behind) had had the not-so-endearing habit of following right behind me. This meant whenever I had to stop, his front tire would hit my back one. This time, biking along on pitch-black black top, when my front tire went into a water-filled hole I had not been able to see and my bike flipped forward, depositing me over the handlebars (but luckily on my feet), Igor crashed into the back of it, ramming my own bike into me.

I wish I had taken that bus.

Igor apologized about 700 times.

I picked up my bike and kept going.

After a while, the slight uphill grade we’d been moving on for 20 minutes turned into a downhill one. We coasted the last mile back to our apartment and completed the final challenge of the adventure race: carrying the bikes up the four flights of steps to my apartment.

***

I had come in last and I hadn’t even technically finished the race, having missed five checkpoints. I was cold, sore and extremely tired. Still, looking at the pictures that night and remembering the day, it was a great experience. My adventure race record may be pitiful (I’ve done two and completely finished neither), but it’s something I’d like to get better at, and America is definitely the place for it.

Maybe I’ll start one in Orlando.